2020年ACCA考试业绩管理(基础阶段)专业词汇汇编(5)

发布时间:2020-10-17

各位小伙伴注意了,考试备考已经进入了关键期,现在状态如何啊,今天51题库考试学习网为大家分享2020年ACCA考试业绩管理(基础阶段)专业词汇汇编(5),一起来看看吧。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:Long Term

Assets

【English Terms】

Long Term Assets

【中文翻译】

长期资产

【详情解释/例子】

1. 资产负债表上项目,指公司物业、设备及其他资本资产的价值减折旧。

2. 计划长期在投资组合中持有的股票、债券或其他资产。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:Long Bond

【English Terms】

Long Bond

【中文翻译】

长期债券

【详情解释/例子】

年期 10 年以上的债券,经常指 30 年美国国库券。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:Long Term

Debt

【English Terms】

Long Term Debt

【中文翻译】

长期债务

【详情解释/例子】

需要支付利息、年期超过 1 年的贷款或财务责任。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:Long Term

Liabilities

【English Terms】

Long Term Liabilities

【中文翻译】

长期负债

【详情解释/例子】

资产负债表上的项目,指公司的租赁、债券偿还及其他超过1 年后到期的负债。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:Lot

【English Terms】

Lot

【中文翻译】

交易单位、批

【详情解释/例子】

一般指组成一宗交易的货品或服务组合。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:M3

【English Terms】

M3

【中文翻译】

货币供应量 3

【详情解释/例子】

货币供应的一种,包括货币供应量2,加所有大额定期存款、机构性货币市场基金、短期购回协议,以及较大型流通资产。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:MTM

【English Terms】

Mark to Market (MTM)

【中文翻译】

以市值计价

【详情解释/例子】

1.根据当时市场价值纪录一种证券、投资组合或账户的价格或价值。

2.交易商计算买卖收益及损失,以及在交易商的报税表上申报这些收益及损失的会计方法。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:Marginal

Utility

【English Terms】

Marginal Utility

【中文翻译】

边际效用

【详情解释/例子】

消费者使用多一个单位的产品或服务可带来的额外满足感。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:Management

Fee

【English Terms】

Management Fee

【中文翻译】

管理费用

【详情解释/例子】

共同基金经理就提供的服务向投资者收取的定额费用。

ACCA财经词汇汇编:Manager

Universe(Benchmark)

【English Terms】

Manager Universe(Benchmark)

【中文翻译】

管理人基准比较

【详情解释/例子】

将户口的表现与具代表性的同类资金经理群作比较。

以上就是51题库考试学习网带给大家的全部内容,相信小伙伴们都了解清楚。预祝大家12月份ACCA考试取得满意的成绩,如果想要了解更多关于ACCA考试的资讯,敬请关注51题库考试学习网!

下面小编为大家准备了 ACCA考试 的相关考题,供大家学习参考。

(ii) the factors that should be considered in the design of a reward scheme for BGL; (7 marks)

(ii) The factors that should be considered in the design of a reward scheme for BGL.

– Whether performance targets should be set with regard to results or effort. It is more difficult to set targets for

administrative and support staff since in many instances the results of their efforts are not easily quantifiable. For

example, sales administrators will improve levels of customer satisfaction but quantifying this is extremely difficult.

– Whether rewards should be monetary or non-monetary. Money means different things to different people. In many

instances people will prefer increased job security which results from improved organisational performance and

adopt a longer term-perspective. Thus the attractiveness of employee share option schemes will appeal to such

individuals. Well designed schemes will correlate the prosperity of the organisation with that of the individuals it

employs.

– Whether the reward promise should be implicit or explicit. Explicit reward promises are easy to understand but in

many respects management will have their hands tied. Implicit reward promises such as the ‘promise’ of promotion

for good performance is also problematic since not all organisations are large enough to offer a structured career

progression. Thus in situations where not everyone can be promoted there needs to be a range of alternative reward

systems in place to acknowledge good performance and encourage commitment from the workforce.

– The size and time span of the reward. This can be difficult to determine especially in businesses such as BGL

which are subject to seasonal variations. i.e. summerhouses will invariably be purchased prior to the summer

season! Hence activity levels may vary and there remains the potential problem of assessing performance when

an organisation operates with surplus capacity.

– Whether the reward should be individual or group based. This is potentially problematic for BGL since the assembly

operatives comprise some individuals who are responsible for their own output and others who work in groups.

Similarly with regard to the sales force then the setting of individual performance targets is problematic since sales

territories will vary in terms of geographical spread and customer concentration.

– Whether the reward scheme should involve equity participation? Such schemes invariably appeal to directors and

senior managers but should arguably be open to all individuals if ‘perceptions of inequity’ are to be avoided.

– Tax considerations need to be taken into account when designing a reward scheme.

2 (a) Discuss the nature of the financial objectives that may be set in a not-for-profit organisation such as a charity

or a hospital. (8 marks)

2 (a) In the case of a not-for-profit (NFP) organisation, the limit on the services that can be provided is the amount of funds that

are available in a given period. A key financial objective for an NFP organisation such as a charity is therefore to raise as

much funds as possible. The fund-raising efforts of a charity may be directed towards the public or to grant-making bodies.

In addition, a charity may have income from investments made from surplus funds from previous periods. In any period,

however, a charity is likely to know from previous experience the amount and timing of the funds available for use. The same

is true for an NFP organisation funded by the government, such as a hospital, since such an organisation will operate under

budget constraints or cash limits. Whether funded by the government or not, NFP organisations will therefore have the

financial objective of keeping spending within budget, and budgets will play an important role in controlling spending and in

specifying the level of services or programmes it is planned to provide.

Since the amount of funding available is limited, NFP organisations will seek to generate the maximum benefit from available

funds. They will obtain resources for use by the organisation as economically as possible: they will employ these resources

efficiently, minimising waste and cutting back on any activities that do not assist in achieving the organisation’s non-financial

objectives; and they will ensure that their operations are directed as effectively as possible towards meeting their objectives.

The goals of economy, efficiency and effectiveness are collectively referred to as value for money (VFM). Economy is

concerned with minimising the input costs for a given level of output. Efficiency is concerned with maximising the outputs

obtained from a given level of input resources, i.e. with the process of transforming economic resources into desires services.

Effectiveness is concerned with the extent to which non-financial organisational goals are achieved.

Measuring the achievement of the financial objective of VFM is difficult because the non-financial goals of NFP organisations

are not quantifiable and so not directly measurable. However, current performance can be compared to historic performance

to ascertain the extent to which positive change has occurred. The availability of the healthcare provided by a hospital, for

example, can be measured by the time that patients have to wait for treatment or for an operation, and waiting times can be

compared year on year to determine the extent to which improvements have been achieved or publicised targets have been

met.

Lacking a profit motive, NFP organisations will have financial objectives that relate to the effective use of resources, such as

achieving a target return on capital employed. In an organisation funded by the government from finance raised through

taxation or public sector borrowing, this financial objective will be centrally imposed.

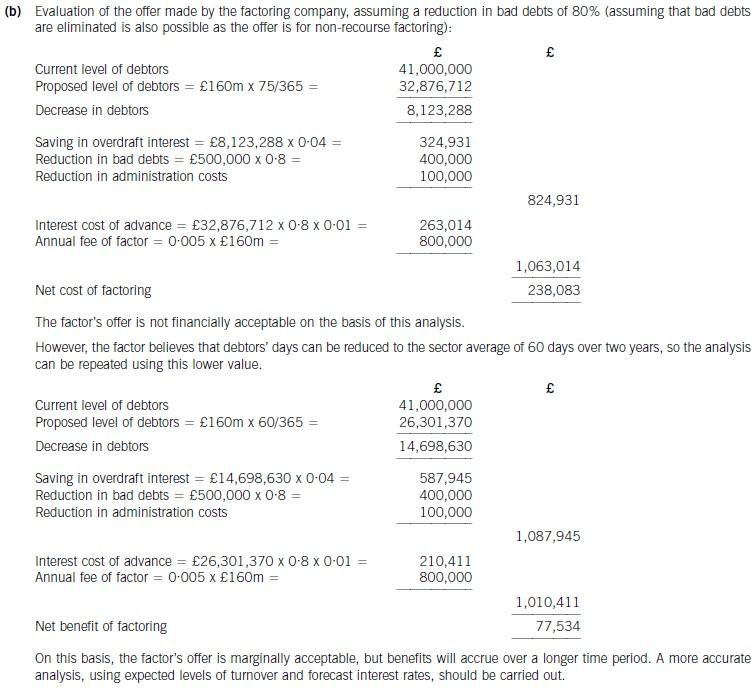

(b) Determine whether the factoring company’s offer can be recommended on financial grounds. Assume a

working year of 365 days and base your analysis on financial information for 2006. (8 marks)

1 Stuart is a self-employed business consultant aged 58. He is married to Rebecca, aged 55. They have one child,

Sam, who is aged 24 and single.

In November 2005 Stuart sold a house in Plymouth for £422,100. Stuart had inherited the house on the death of

his mother on 1 May 1994 when it had a probate value of £185,000. The subsequent pattern of occupation was as

follows:

1 May 1994 to 28 February 1995 occupied by Stuart and Rebecca as main residence

1 March 1995 to 31 December 1998 unoccupied

1 January 1999 to 31 March 2001 let out (unfurnished)

1 April 2001 to 30 November 2001 occupied by Stuart and Rebecca

1 December 2001 to 30 November 2005 used occasionally as second home

Both Stuart and Rebecca had lived in London from March 1995 onwards. On 1 March 2001 Stuart and Rebecca

bought a house in London in their joint names. On 1 January 2002 they elected for their London house to be their

principal private residence with effect from that date, up until that point the Plymouth property had been their principal

private residence.

No other capital disposals were made by Stuart in the tax year 2005/06. He has £29,500 of capital losses brought

forward from previous years.

Stuart intends to invest the gross sale proceeds from the sale of the Plymouth house, and is considering two

investment options, both of which he believes will provide equal risk and returns. These are as follows:

(1) acquiring shares in Omikron plc; or

(2) acquiring further shares in Omega plc.

Notes:

1. Omikron plc is a listed UK trading company, with 50,250,000 shares in issue. Its shares currently trade at 42p

per share.

2. Stuart and Rebecca helped start up the company, which was then Omega Ltd. The company was formed on

1 June 1990, when they each bought 24,000 shares for £1 per share. The company became listed on 1 May

1997. On this date their holding was subdivided, with each of them receiving 100 shares in Omega plc for each

share held in Omega Ltd. The issued share capital of Omega plc is currently 10,000,000 shares. The share price

is quoted at 208p – 216p with marked bargains at 207p, 211p, and 215p.

Stuart and Rebecca’s assets (following the sale of the Plymouth house but before any investment of the proceeds) are

as follows:

Assets Stuart Rebecca

£ £

Family house in London 450,000 450,000

Cash from property sale 422,100 –

Cash deposits 165,000 165,000

Portfolio of quoted investments – 250,000

Shares in Omega plc see above see above

Life insurance policy note 1 note 1

Note:

1. The life insurance policy will pay out a sum of £200,000 on the death of the first spouse to die.

Stuart has recently been diagnosed with a serious illness. He is expected to live for another two or three years only.

He is concerned about the possible inheritance tax that will arise on his death. Both he and Rebecca have wills whose

terms transfer all assets to the surviving spouse. Rebecca is in good health.

Neither Stuart nor Rebecca has made any previous chargeable lifetime transfers for the purposes of inheritance tax.

Required:

(a) Calculate the taxable capital gain on the sale of the Plymouth house in November 2005 (9 marks)

Note that the last 36 months count as deemed occupation, as the house was Stuart’s principal private residence (PPR)

at some point during his period of ownership.

The first 36 months of the period from 1 March 1995 to 31 March 2001 qualifies as a deemed occupation period as

Stuart and Rebecca returned to occupy the property on 1 April 2001. The remainder of the period will be treated as a

period of absence, although letting relief is available for part of the period (see below).

The exempt element of the gain is the proportion during which the property was occupied, real or deemed. This is

£138,665 (90/139 x £214,160).

(2) The chargeable gain is restricted for the period that the property was let out. This is restricted to the lowest of the

following:

(i) the gain attributable to the letting period (27/139 x 214,160) = £41,599

(ii) £40,000

(iii) the total exempt PPR gain = £138,665

i.e. £40,000.

(3) The taper relief is effectively wasted, having restricted losses b/f to preserve the annual exemption.

声明:本文内容由互联网用户自发贡献自行上传,本网站不拥有所有权,未作人工编辑处理,也不承担相关法律责任。如果您发现有涉嫌版权的内容,欢迎发送邮件至:contact@51tk.com 进行举报,并提供相关证据,工作人员会在5个工作日内联系你,一经查实,本站将立刻删除涉嫌侵权内容。

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-17

- 2019-01-04

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-18

- 2019-01-04

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-17

- 2019-01-04

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-18

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-17

- 2020-10-18