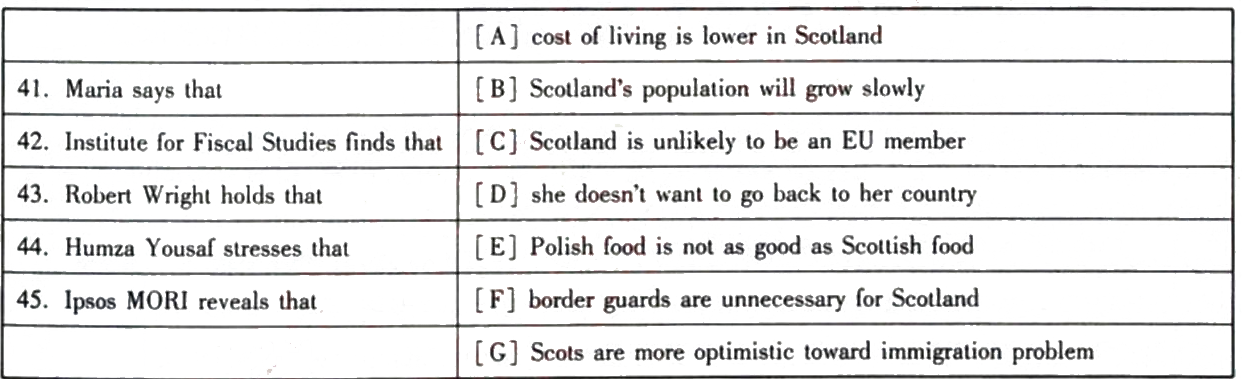

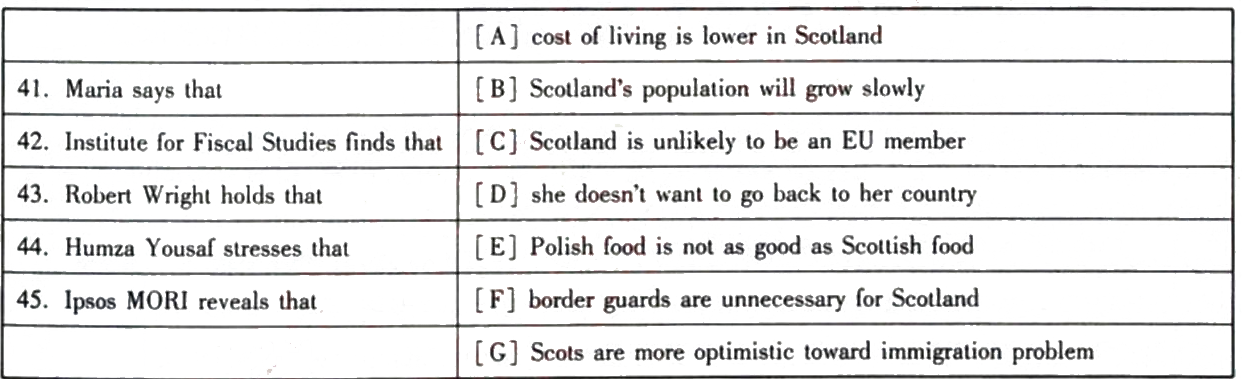

At the Polish Club in Glasgow,Scots and Poles socialize easily.Many of the customers in its restaurant are Scotlish,eager to try Polish food before going there on holiday,says 16-year-old Mari-a,who moved to Scotland eight years ago and works in the club part-time as a waitress.She,by contrast,has no desire to retum.Scotland's welcome has been warm.Its govemmenl wants it to be warmer still.Scotland's leaders h8ve long mainLained that they need immigrants more ihan the rest of Britain does,both to boost the country's sparse population and to alleviate skiUs shortages.Between 1981 and 2003 Scotland's population declined.Most of Lhe population growth that Scodand has seen since then has been thanks to migrants,largely from outside Britain.Scots are having fewer children and ageing more rapidly than other Britons:on current trends the Scottish population will swell by just 4%by 2062 compared with 23qo for Britain as a whole,according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.The only group expected to grow is the oldest one.If Scots vote for independence,a nationalist govemment promises to encourage immigraLion.It would offer incentives for migrants willing to move to far-flung spoLs.It would ease the nationwide requirement that immigrants must earn a particular salary to gain residency to reflect the lower cost of living there.Students would be able to stay after graduating and work for several years.Turning these aspirations into a workable immigraLion policy would be tricky.Though anxious to join the EU,Scotland's government is less keen on the Schengen travel zone,which allows non-EU ciUzens to travel on a single visa.It wants to remain part of the Common Travel Area,like the Republic oflreland,which imposes minimal border controls.Robert Wright,an economist at Strathclyde Uruversity who has advised the government on demography,is unconvinced this pick-and-mix approach to EU membership would work.And this would be one of many strains on Scotland's relationship with the rest of Britain.Different immigration policies in two countries that share a land border could result in stricter controls,including passport checks between them.Humza Yousaf,Scodand's minister for extemal affairs and international development,denies they would be necessary.Scotland would have border management,he stresses,not border guards.But some English politicians may disagree.If the nationalists lose the independence vote,London could be minded to devolve further powers to Scodand,perhaps including over immigration.Mr Wnght argues there is scope for more regional diversity.In Canada,immigraLion requirements are eased if people agree to live in less popular provinces.Scots are somewhat less resisLant to immigration Lhan other Britons.Some 58%want fewer migrants in ScoLland.Fully 75qo of English and Welsh people want fewer in their countries,says a report by the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford.And Scots are more sanguine.Just 21%identify immigration as one of Lhe most important issues facing the country,lower than the British average of 33%,according to Ipsos MORI,a pollster.Thal equanimity stems in part from the fact that migrants in Scotland are not especially common.More than half of its"foreign"residents come from other parts of Britain.Attitudes to immigrants tend to be softest where newcomers are scarce,as in Scotland,or very numerous,as in London.They harden in between those extremes.In eastern England,for example,where eastern Europeans are increasingly numerous,38%fume about immigration.If Scotland manages to entice more foreigners,it will enter this difficult middle territory.The warm Scottish welcome could cool.

Robert Wright holds that